Amid Australia’s justified concern over male violence against women, we should remember how much we have been able to achieve so far. Some important indicators of violence against women have more than halved in the past three decades.

Prologue: Violence against women is a bad thing, and it’s still bad even when it used to be worse. We should be trying hard to lower rates of violence, by finding good solutions and implementing them with urgency. We should also understand just what we’re dealing with – which is what this summary tries to do.

The issue of violence against women is in the news right now. Here’s a short summary of what we know about the issue in Australia.

- Before we say anything else, we need to acknowledge this: an accurate picture of violent crime is hard to get at for several reasons, but mostly because most official crime figures are so very, very unreliable. That goes double for violence against women. Many crimes never get reported, or the police don’t charge anyone, or judges and juries don’t convict – and all of these things change over time as society changes.

- It’s hard to exaggerate what a problem this is. My strong impression is that most of the public and many commentators expect government crime statistics will tell us everything we need to know. They never do.

- How bad is the problem? One typical analysis claims that “about 70% of domestic violence is never reported to the police.” You can probably come up with plenty of reasons why this figure is so high.

- Rates of reporting, charging and convicting thus affect the figures far more than do underlying changes in the actual level of violence in Australia.

- The result of all that is that most experts don’t trust all the official statistics to give them an accurate read on what’s happening. Instead they look for the most reliable figures – which are, necessarily, the figures that will suffer least from under-reporting. That leads them to the figures for homicides. These suffer less from under-reporting, simply because it’s hard to avoid people noticing when someone dies.

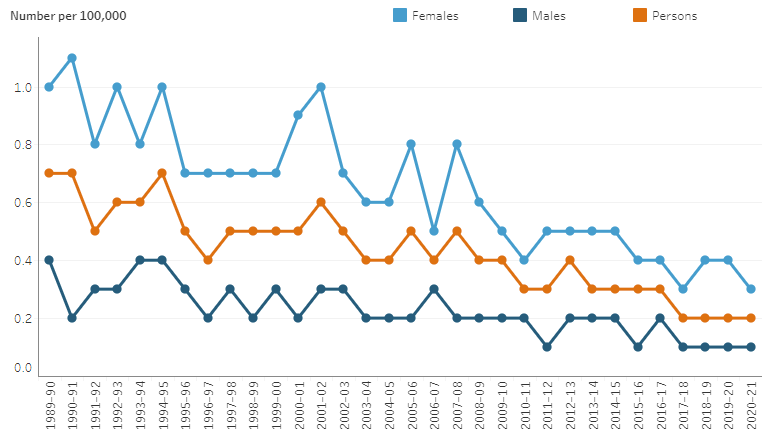

- The homicide indicators suggest Australian violence against women continues to fall, at a speed that might surprise many people. Among the most reliable indicators is intimate partner homicide; female victims are down 60+% in the 31 years to 2020-21. (Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare)

Intimate partner homicide, 1989-90 to 2020-21

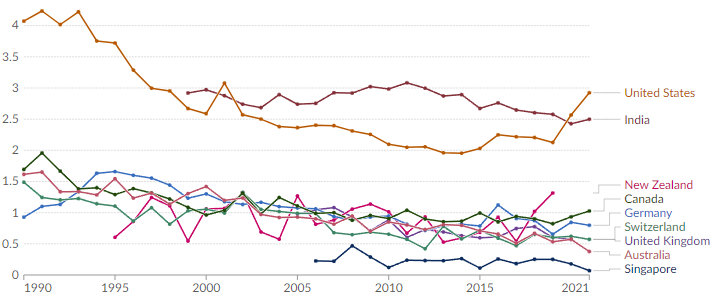

Figure from AIHW

- When we step back and look at other countries, it’s not clear that Australia has done badly at reducing violence against women. The female victim homicide rate is falling in many places around the world. And countries like Singapore show how much better we should be able to do. But not that many places have bettered Australia’s rate of change over the past 15 years. (At the same time, we shouldn’t pat ourselves on the back too hard – because we really just don’t know what causes violent crime numbers to move around over the decades in any country, ours included.)

Female homicide rate, 1990 to 2021, per 100,000 women, for Australia and comparator nations

Figure from Our World In Data

- News reports on the Anzac Day weekend featured a figure of “26 women allegedly killed by men in the first 115 days of the year”. I don’t know how reliable that number is. But on my initial maths, if that rate of homicide continued through 2024, it would mean 83 female victims of homicide for Australia this year – a rate of .59 female homicides per 100,000 women. That is horrific, but not notably out of line with other recent years, such as 202-21’s 69. It would have been a record low just a few years ago.

- As the graph on intimate partner homicide above shows, these homicide figures jump around quite a bit from year to year, largely because the numbers are not bigger. The numbers jump around even more from quarter to quarter. I haven’t yet seen anyone claim that some happened at the start of 2024 to drive the figures notably higher. I’m not sure it’s a good idea to suggest on the basis of events to date that this is happening, unless you have a fairly decent chain of reasoning.

- We do have one more fairly reliable source of domestic violence data – the Personal Safety Survey done every five years by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This tries to avoid the police crime figures issues by coming at the problem from the other end: it asks members of the general public what crimes they have experienced. As Ben Spivak at the Swinburne Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science notes, the survey numbers suggest at worst that overall domestic violence rates are not rising, and at best that they are falling over time. For instance, the rate of cohabiting partner violence against women fell from 1.7% in 2016 to 0.9% in 2021-22.

- Some analysts nevertheless cite police crime data to argue that the analysis above goes astray. This argument says that rises over the past decade in rates of male offending in categories like “sexual assault and related offences”, “abduction and harassment” and “acts intended to cause injury” suggest these types of male violence against women are moving up, even as homicide rates move down. That is, they argue that changes in reporting rates don’t explain these numbers. This is possible. But it does not seem all that likely to me that homicide has detached itself so thoroughly from other violence indicators.

- My expectation is that the official levels of these non-homicide offences are rising because our efforts to raise reporting, charging and conviction rates are actually bearing fruit – that is, less crimes are slipping through the cracks. But this is the one point that I most want to explore further, and if necessary revise in this post.

- To the extent that the homicide indicators a) indicate actual crime levels and b) are at odds with people’s perceptions, commentators and the media should work to make both the figures and people’s perceptions more accurate. The stories we tell about crime rates have a real impact on people’s lives. As crime academics Terry Goldsworthy and Gaell Brotto have noted, a person’s fear of current crime levels can be influenced by a number of things, including media exposure. Don Weatherburn, former head of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research has argued: “The female homicide rate is much lower now than it was 20 years ago. The media never report this.’

All of this matters for Australia’s current domestic violence discussion. But it also matters every time some politician or commentator – Left or Right, and historically it has more often been Right – makes a claim about the violent crime rate. We’re in a new era of lower crime, and the debate should recognise that fact.

* The author studied criminal statistics at the University of Adelaide and has dealt with statistics and their presentation in various roles for more than 30 years.